The introduction of the UK’s new Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing, Access and Growth (VPAG) has led to a number of questions – not only as to how this compares with the Statutory Scheme, but in particular, the broader implications and longer-term impact of such measures on patients’ access to new medicines. The Red Nucleus Market Access and Commercialization team provide a summary of the VPAG characteristics and consider what this means for the industry’s commercial ambitions within the UK, as well as potential implications for patients.

What are the UK’s clawback schemes?

The VPAG and Statutory Schemes are the UK’s two cost-containment schemes for branded medicines. Both limit annual growth of expenditure by the NHS to predefined limits, with manufacturers having to payback a percentage of branded medicine sales above this rate to safeguard the financial position of the NHS.

The VPAG scheme

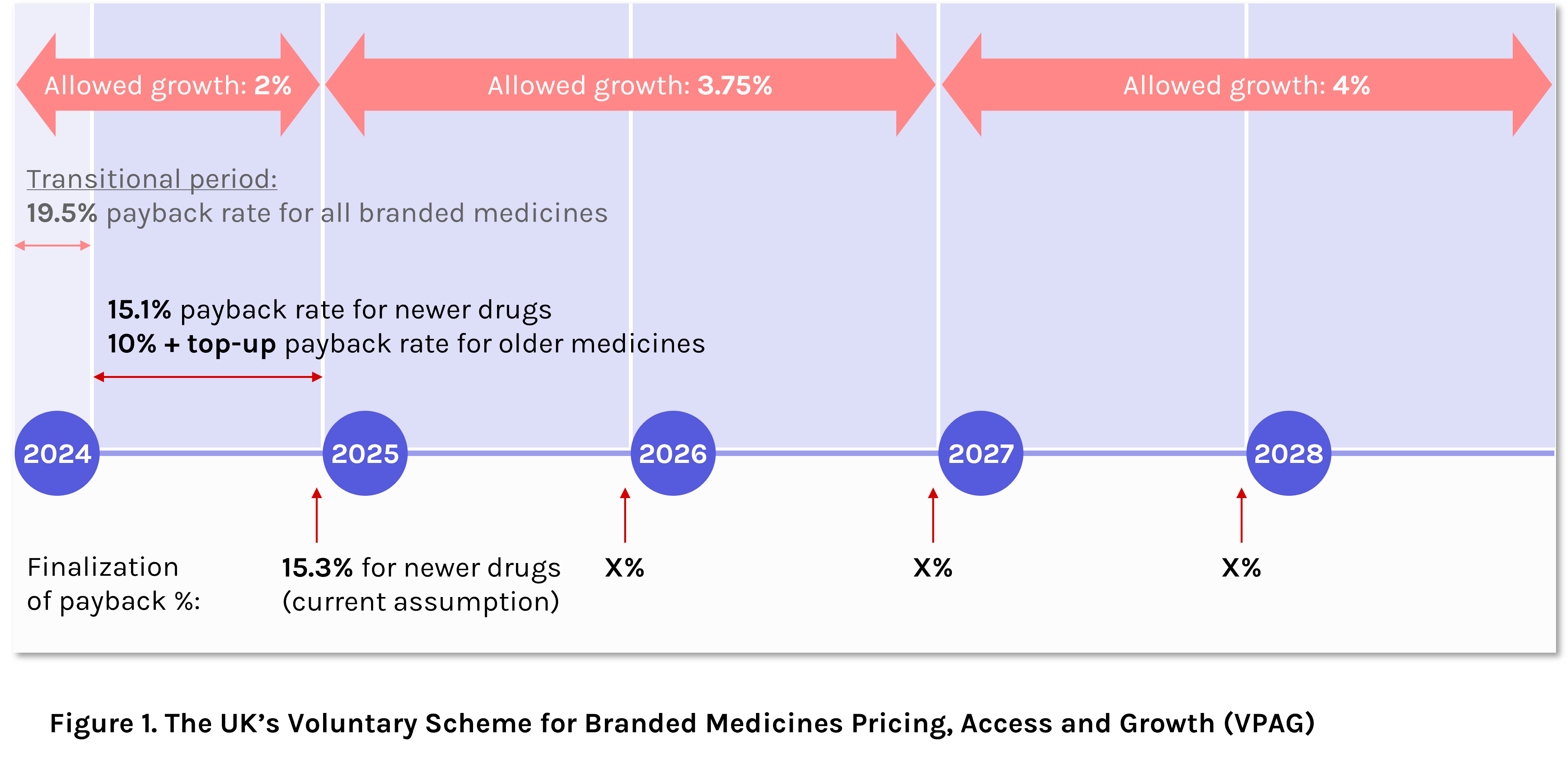

The VPAG is the newest iteration of the UK’s non-contractual cost-containment scheme, running between 2024 and 2028. Compared with the scheme’s predecessor (the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access, VPAS), the VPAG offers a higher level of allowed annual growth of expenditure, starting at 2% in 2024 (equivalent to VPAS), but doubling to 4% by 2027-2028.

Beginning 1st January 2024, the UK entered into the initial three-month transitional period of the VPAG scheme, whereby the payback rate for all branded medicines was set to 19.5%. As of the 1st April, differential clawback rates came into effect, based on medicine novelty (or perceived level of innovation) and price decline of older medicines (Figure 1).

The Statutory Scheme

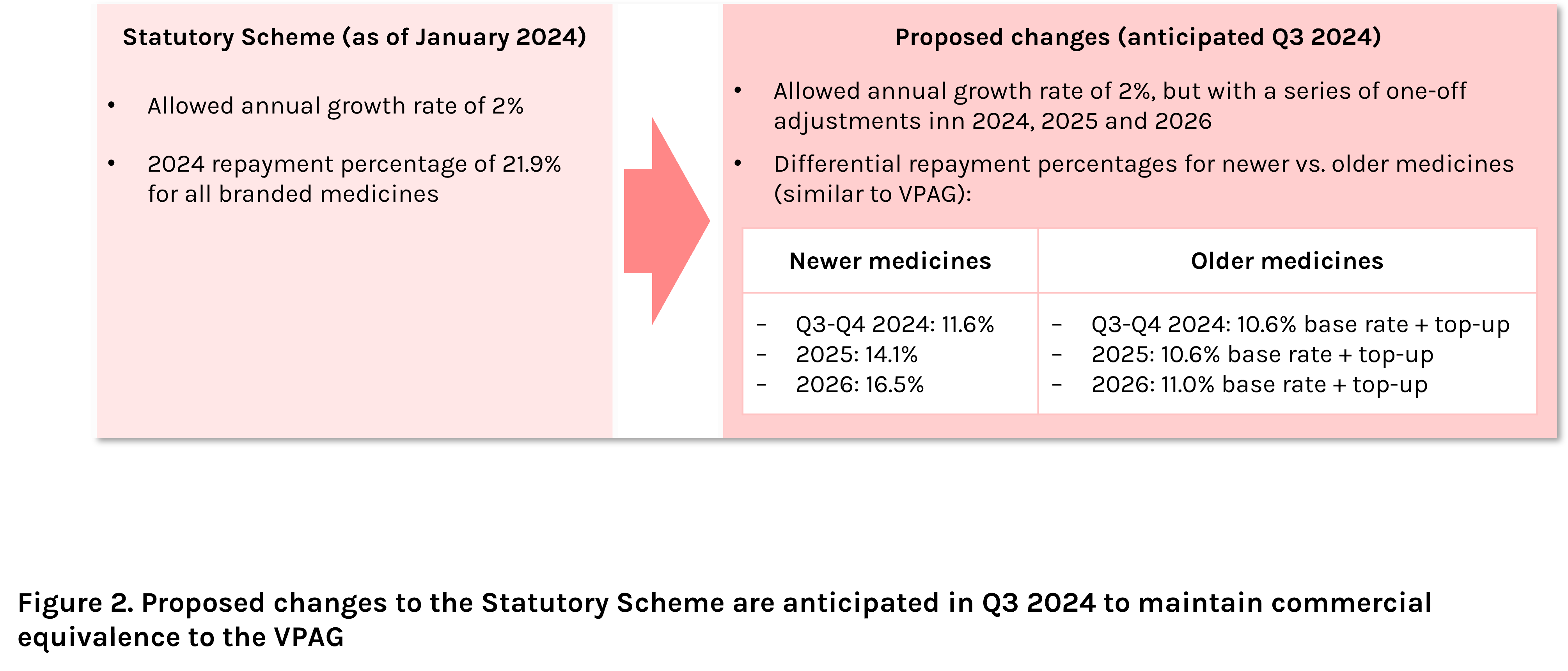

Companies who choose not to opt into the voluntary scheme are subject to the Statutory Scheme, with the terms imposed by law, rather than as a result of collaborative negotiations between the UK government and the British pharmaceutical industry.

With the recent updates to the VPAG scheme, the Statutory Scheme is currently under consultation to maintain commercial equivalence to VPAG, with changes expected in Q3 2024 (Figure 2).

What do differential clawback rates mean for the UK pharmaceutical industry?

Within the current VPAG period, “newer” medicines are required to pay back a flat rate of 15.1% of annual sales in a process similar to the old VPAS scheme, but with a significantly lower clawback percentage.

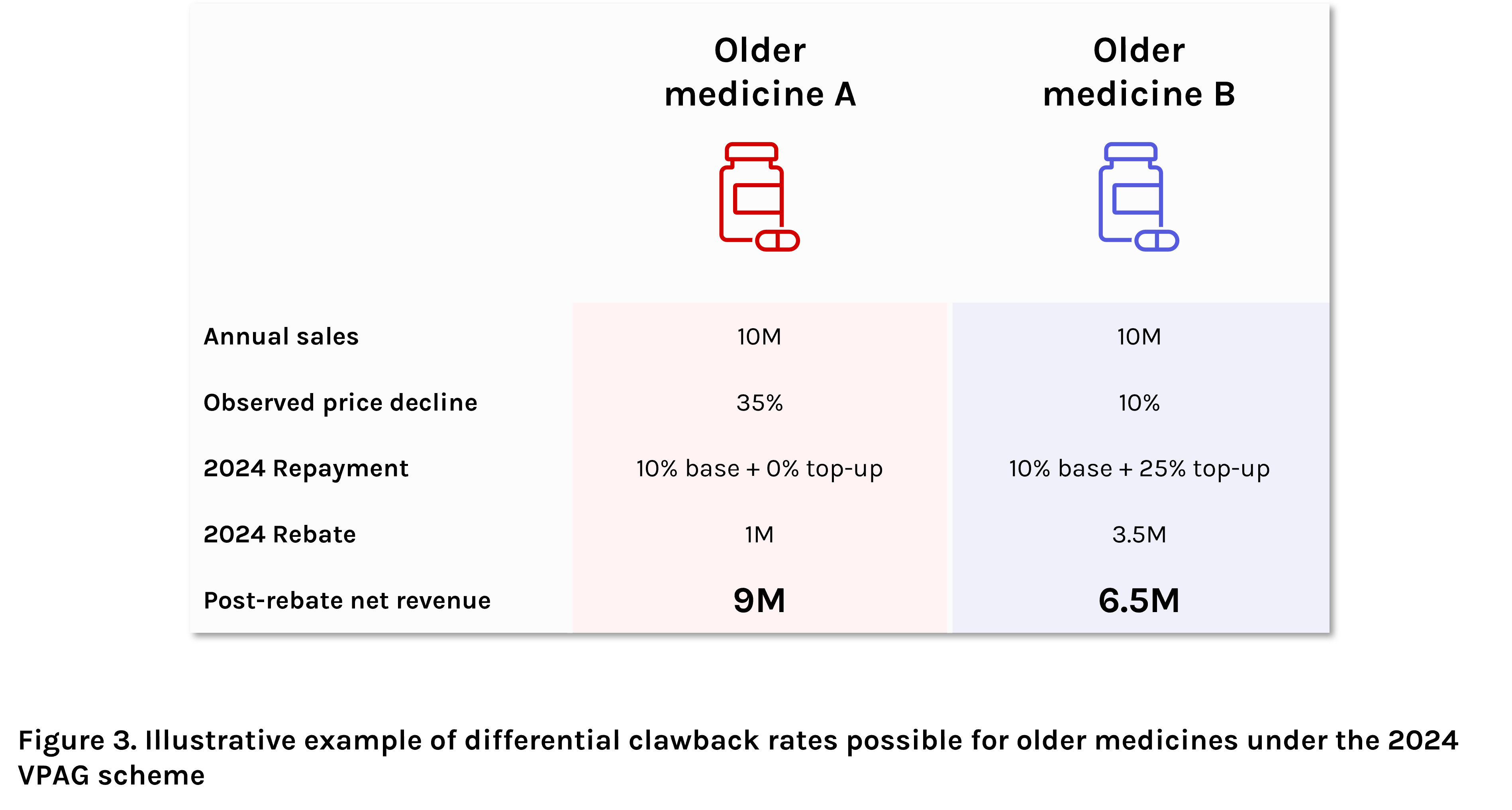

For “older” medicines, the process gets more complex. Here, a base payback rate of 10% applies, but with potential for a linear sliding scale top-up rate based on the observed price decline – i.e., the differential between the observed average selling price of the branded presentation compared to the reference price. For products within 10% of the reference price, the maximum 25% top-up percentage applies. Each percentage point increase in observed price decline results in a 1% reduction in top-up rate, with no top-up amount for products costing at least 35% less than their reference price. Overall, these potential differences in total rebate percentage for older medicines are likely to lead to vast differences in post-rebate net revenue potential for the manufacturers of these products (Figure 3).

Is the new VPAG Scheme a “good” compromise?

The VPAG allowed growth rate represents a clear compromise between the UK government and the pharmaceutical industry. Although allowed growth of drug expenditure will double from 2% in 2024 to 4% by 2027, this is still well below the expected growth rate of expenditure, currently forecast at 6% in the same year. Although increases in allowed growth rate are a step in the right direction, this ongoing shortfall ultimately means annual increases in repayment rates are inevitable.

Or could it lead to a reduction in choice?

The clawback rates set out in the new VPAG scheme (as well as proposed Statutory Scheme rates) for newer, or more innovative, medicines represent a huge improvement over the unprecedented level of 26.5% reached by the scheme’s predecessor, the VPAS, in 2023. However, for older, or less innovative, medicines, manufacturers risk much larger payback percentages and substantially lower post-rebate net revenue, potentially leading manufacturers of these medicines to de-prioritise the UK in their market access planning. In an extreme scenario, this could lead to reduced availability of older, often more economically priced medicines, leaving predominantly higher cost alternatives and inadvertently increasing overall drug expenditure. Indeed, recent UK drug shortages, including medicines critical in treating ADHD, diabetes and epilepsy, were exacerbated by manufacturers removing the UK from their supply chains – something which could become more common with reduced incentives for select medicines.

Can the UK remain attractive as an early recipient of innovative products?

Overall, the new VPAG agreement was the result of intense industry pressure following a surge in repayment rates in 2023 to over a quarter of industry total revenue (clawbacks totaled £3.3 billion in 2023 compared to £0.6billion in 2021). This resulted in industry concerns around loss of competitiveness for UK pharma versus other European countries, where industry levy is significantly lower. However, although lower clawback rates for new medicines may help attract greater innovation to the UK, these rates are still amongst the highest in Europe, and manufacturers of older medicines risk even higher rebates. With anticipated updates to the Statutory Scheme to maintain its commercial equivalence to the VPAG, the UK’s two cost-containment schemes will continue to be an integral consideration in market access strategy.

Outlook

Cost containment measures are inevitable, especially given the current economic conditions both globally and in the UK. However, these must be balanced against ensuring patient care is not compromised – for example, through more limited or delayed access to innovative products, or through reduced access to older, more established treatments. For manufacturers, these pressures are not new, and VPAG offers a measured step forward, but this may not be enough to tip the scales firmly back in favor of the patient.

By Kate Cullen, PhD (Associated Consultant), Red Nucleus Market Access & Commercialization Services

Supported by Higia Vassoler (Associate Director) and Frank Cousins (Vice President)

Contact us to find out more about how our Market Access and Commercialization Services team can support you with your access strategy

Sources

- Department of Health and Social Care (2023) 2024 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing, Access and Growth. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2024-voluntary-scheme-for-branded-medicines-pricing-access-and-growth (Accessed April 2024).

- Department of Health and Social Care (2023) Proposed update to the statutory scheme to control the cost of branded health service medicines, open consultation. Available at: Proposed update to the statutory scheme to control the cost of branded health service medicines - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) (Accessed April 2024).